Originally published by Daily Guardian

Did you know that the largest bat of all is found only in the Philippines? Planet Earth has 1400 known bat species and the Golden-crowned Flying Fox (Acerodon jubatus) earns the top spot for size and weight. Known locally as kabog, it is endemic or found nowhere else but in the Philippines.

Strikingly patterned with a golden cap, reddish fur and chocolate-brown wings, adults weigh over a kilogram and can boast of a wingspan nearly two meters across – longer than most people are tall.

“The Philippines has 79 recorded bat species, half of them endemic,” explains Dr. Mariano Roy Duya of the University of the Philippines Institute of Biology (UPIB). North America, with a land area that is 66 times larger – has but 45. We have an incredible diversity of bats since each of our 7100 islands is geographically unique. And of course, we have the largest bat of all.”

Once widespread throughout undisturbed lowland forests across the country, hunting and deforestation – particularly from slash-and-burn upland farming or kaingin – have whittled down bat populations.

Dumaguete-based filmmaker Rhiyad Maturan and I were recently invited by the Energy Development Corporation (EDC) to film a thriving kabog colony inside the Bacon-Manito Geothermal Project, a heavily forested geothermal reservation nestled between the provinces of Albay and Sorsogon on the island of Luzon. Though the area is now verdant and alive, it wasn’t always so.

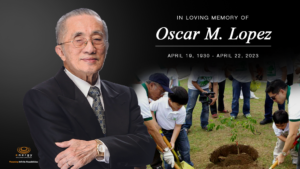

“Believe it or not, that entire mountain range was once logged-over,” says Ed Jimenez, corporate relations head for EDC’s Bacon-Manito Geothermal Project, pointing at well-forested hills nearby. “The only trees left were the ones loggers ignored. To bring the mountains back to life, we worked with the local communities to help reforest this area while providing them with an alternative source of income. Decades later, the organizations we helped form, like the Alliance of Bacman Farmer’s Association Inc. Agriculture Cooperative (formerly ALBAFAI) and the Bacman Host Community Multi-purpose Cooperative (BMPC), have become some of our most passionate champions. Even the grandchildren of the original members are helping us plant trees, promote community-based conservation and protect these forests.”

Aside from bats, Bicol’s forests also shelter wild deer, pigs, monkeys and birds – most of which were driven to remote areas by decades of hunting and forest loss.

“I learned to shoot kabog with an airgun when I was still a kid,” recalls Joseph ‘Doy’ Gabion, a former bat hunter. “Bats are easy to hunt by day because they hang upside down from their roosts. When the roosts were eventually protected by EDC and its conservation partners, we hunters had to wait until the bats flew out to their feeding grounds. Back in the 1990s, my uncle and I would wait for them to pass to be able to catch two or three bats a night. Kabog meat has a slightly woody taste.” Doy has since stopped hunting and now volunteers with the Armed Forces of the Philippines’ CAFGU Active Auxiliary Unit II to help protect the very animals he once hunted.

The kabog colony moves from one area to another within the Bacman reservation and we chanced upon them roosting on a grove of pine-like Agoho (Casuarina spp.) trees. “We have about 700 kabog individuals here now, our flagship fauna species for this site,” explains Forester Neil Miras, EDC Bacman’s watershed management officer.

Representing iconic wildlife found in its geothermal, solar and wind sites, EDC’s Flagship Species Initiative (FSI) aims to popularize some of the nation’s lesser-known forest denizens. The eight other flagship species include the Philippine Warty Pig (Sus philippensis), Visayan Hornbill (Penelopides panini), Apo Myna (Goodfellowia miranda), plus native trees like Mapilig (Xanthostemon bracteatus), Katmon Bayani (Dillenia megalantha), Red Lauan (Shorea negrosensis), Almaciga (Agathis philippinensis) and Igem-dagat (Podocarpus costalis). EDC has been planting native trees across the country since the 1980s.

“Though millions of trees have been planted under the BINHI Program, we should still recognize the importance and effectiveness of natural seed dispersion – either by the wind, water or by local wildlife,” explains Forester Abegail Gatdula, EDC-FSI project manager. “Flying animals like birds and bats eat the fruits of various forest trees and disperse them far and wide within life-giving guano bombs, giving the seeds a vital headstart.”

Though not as popular as the Tamaraw or Philippine Eagle, the kabog has been quietly doing its part to make the Philippines greener. “Think of them as the ‘silent seed planters’ of nature. We never pay them but they keep working for our world,” concludes Jean Dayap, Municipal Environment and Natural Resources Officer (MENRO) of Manito in Albay.

So tonight, please look up at the night sky to thank our uncelebrated wildlife heroes, quietly working the night shift to make the Philippines a little greener – one guano bomb at a time.

Watch our Golden-crowned Flying Fox documentary HERE.